Nguồn: https://kimdunghn.wordpress.com/2017/07/11/gap-go-o-ha-noi/

Tác giả: Kỳ Duyên

———–

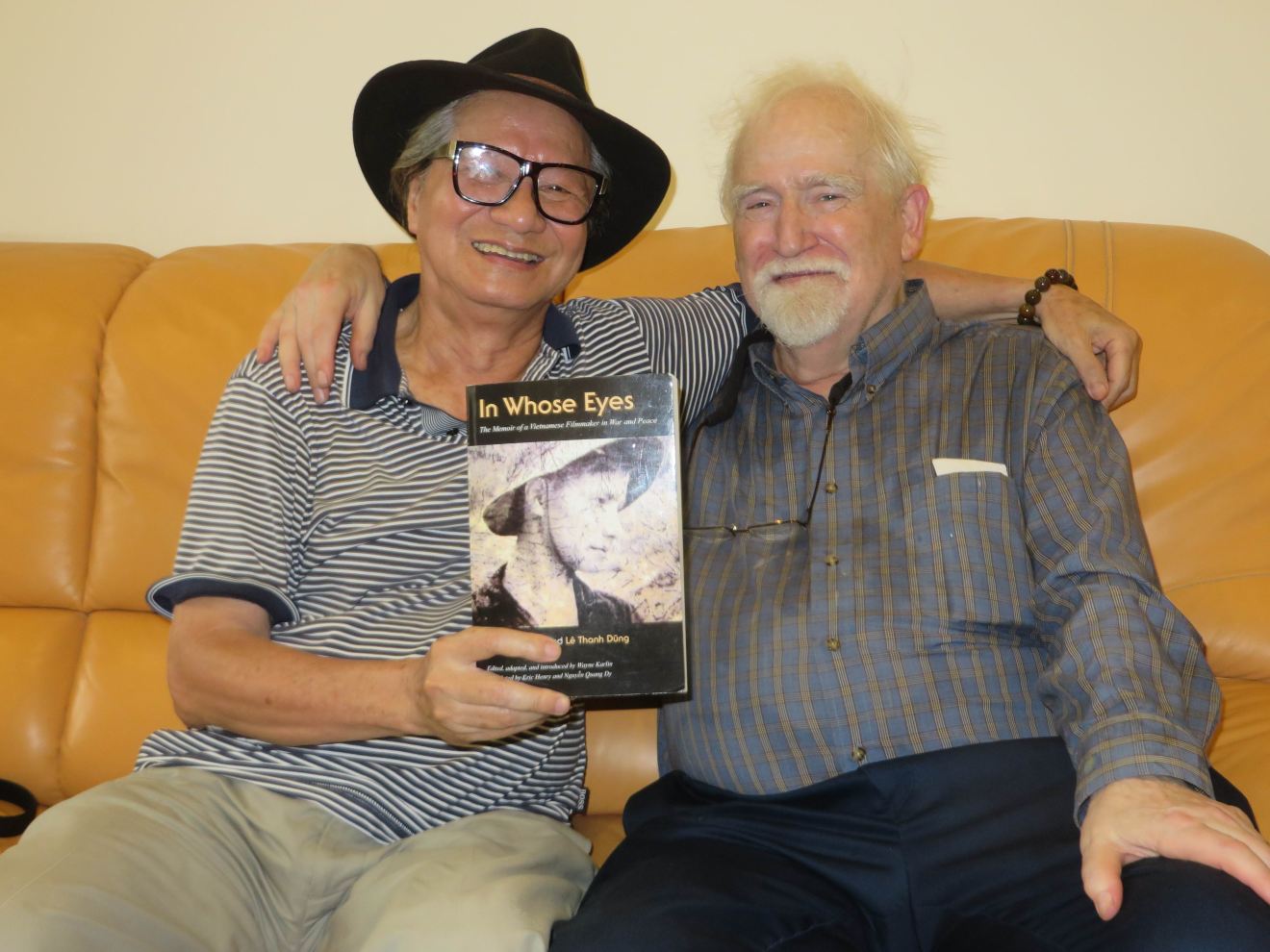

Đó là để nói về cuộc gặp gỡ đầy ân tình của các anh chị em ở Café thứ 05, tổ chức tại gia đình anh chị Gia Hảo- Chi Lan với Eric Henry- một trong ba dịch giả của cuốn sách Trong mắt ai (IN WHOSE EYES) của đạo diễn tên tuổi Trần Văn Thủy, cũng đồng thời là người bạn thân thiết của đạo diễn. Thỉnh thoảng nhóm các anh chị em Café thứ 05 lại "kiếm cớ" gặp nhau cho… thư thái.

Đó là để nói về cuộc gặp gỡ đầy ân tình của các anh chị em ở Café thứ 05, tổ chức tại gia đình anh chị Gia Hảo- Chi Lan với Eric Henry- một trong ba dịch giả của cuốn sách Trong mắt ai (IN WHOSE EYES) của đạo diễn tên tuổi Trần Văn Thủy, cũng đồng thời là người bạn thân thiết của đạo diễn. Thỉnh thoảng nhóm các anh chị em Café thứ 05 lại "kiếm cớ" gặp nhau cho… thư thái.

Bất ngờ nhất với tôi, là sự xuất hiện của nhà thơ Bùi Minh Quốc- người có những bài thơ nổi tiếng, những câu thơ "nổi tiếng" và cũng là người vốn luôn được "chăm sóc đặc biệt". Lần đầu tiên tôi gặp trực tiếp ông ở ngoài đời. Nhưng Bài thơ về Hạnh phúc quá nổi tiếng của ông, từng làm thổn thức con tim bao thế hệ một thời chiến tranh, và bản thân người viết bài này, từng dẫn chứng lại trong một bài báo trên Tuần Việt Nam cũng về chủ đề Hạnh phúc.

Cho dù, có thể quan niệm khác nhau, cách sống khác nhau, nhưng điều quan trọng nhất là cái tình gắn bó của mọi người với các vị khách phương xa, với nhau- không phân biệt tuổi tác, không phân biệt thân hay sơ.

Eric thì nói tiếng Việt, thạo tiếng Việt gần như một người Việt chính cống. Chính vì thế sẽ chẳng lạ khi giữa chừng bữa ăn với những món ăn Hà Nội tinh tế- do hai chị em gái chị Chi Lan- Chi Mai chủ đạo, nhà thơ Bùi Minh Quốc say sưa đọc cho Eric nghe Bài thơ về Hạnh phúc. Và hai người hí hoáy ghi cho nhau- những gì- chỉ họ mới biết. Eric chăm chú lắng nghe, gật gật. Còn Bùi Minh Quốc, say sưa đọc, với gương mặt đỏ bừng, vì rượu hay vì bầu nhiệt huyết lúc nào cũng tràn đầy?

Hạnh phúc là gì bao lần ta lúng túng

Hỏi nhau hoài nghĩ mãi không ra…

Còn giờ đây, với lứa tuổi của mọi người ở Café thứ 05, hạnh phúc đơn giản lắm, đơn giản đến mức đọc lên những câu thơ của ai đó gửi cho chị Chi Lan, và được chị gửi lại cho mọi người cùng đọc, mà người viết bài này rưng rưng muốn khóc:

BẠN TA

Thăm hỏi Bạn, biết rằng người còn đó

Nỗi mừng vui tràn ngập cõi lòng tôi

Cuộc đời này bao sóng gió, nổi trôi

Vui được biết, Bạn bình an vui sống..

Đời trần thế ví như là huyễn mộng

Kiếp nhân sinh là sinh tử, tử sinh

Quý nhau chăng chỉ ở một chữ Tình

Tình cha mẹ, tình vợ chồng, bè bạn .

Tình cảm ấy ta không treo giá bán

Khi con tim không đơn vị đo lường

Bàn cân nào, cân được chữ Yêu Thương

Thế mới biết Thương Yêu là vô giá!.

Cuộc đời dẫu đảo điên, nhiều dối trá

Nếu chúng ta thực sự mến thương nhau

Thì tiếc chi một lời nói, câu chào

Hãy trao gửi, sưởi ấm tình nhân thế .

Có hơn không dù biết rằng chậm trễ

Vì con người ai cũng thích yêu thương

Được thương người và cũng được người thương

Hãy bày tỏ yêu thương dù có chậm .

Bạn còn đó! Tôi còn đây! Mừng lắm!

Vì chúng ta còn cơ hội gặp nhau

Để trao nhau lời nói với câu chào

Đầy thân ái, đầy yêu thương, quý mến ..

Chuyện dĩ vãng, chuyện tương lai sắp đến

Hãy quên đi, xin nhớ hiện tại thôi

Nếu tâm bình trí lạc! Thế đủ rồi!

Người còn đó! Tôi còn đây! Phúc lắm..

Nhưng với đạo diễn Trần Văn Thủy- người luôn suy tư về thời cuộc với những day dứt trước thế thái nhân tình thì lúc này đây, hạnh phúc giản dị mà ấm áp- có lẽ là khi ông nhận được 02 bản dịch của 02 bài đầu cuốn tiểu thuyết mới nhất của ông vừa xuất bản ở Mỹ với nhan đề "Trong đống tro tàn" được Eric dịch ngay trên chuyến máy bay, bay từ Mỹ đến Sài Gòn. Eric cũng nhờ đạo diễn Trần Văn Thủy chuyển tới mọi người ở Café thứ 05, những ai quan tâm tới cuốn sách với lời cảm ơn và lời chào thân ái.

Và thể theo đề nghị của Đạo diễn Trần Văn Thủy, xin đăng lên cả hai bản dịch (từ tiếng Việt sang tiếng Anh) của Eric để bạn đọc nào có nhu cầu, có thể đọc và chia sẻ

Một cuộc gặp gỡ bạn bè ở Hà Nội, thật nghĩa tình khó quên

Xin đọc hai bản dịch của Eric bằng tiếng Anh:

1- Points That May be observed in "The Heap Dusty Ashes" by Trần Văn Thủy

(Những Gì Thấy Được 'Trong Đống Tro Tàn' Của Trần Văn Thủy)

Phạm Phú Minh

To the best of my knowledge, the writer and film director Trần Văn Thủy is the first person living in the contemporary society of Vietnam who set forth the problem of kindness in his own productions. His documentary film On Being Kind was made in 1985, and after being shown several years later, it created a great upheaval in the consciences of viewers, not just in Vietnam, but in many places around the world.

What does this mean? What is this about kindness? Well then, what is strange about it? Is it not the case that from the time of the creation of Heaven and Earth, human beings have lived amid an endless struggle between Good and Evil—this reminds me of the name of an American film, From Here to Eternity, or as the French render the title, Tant qu'il y aura des hommes—as long as there are people—as long as people still exist. The English and French titles of this famous film both allow us to see that the conflict between Good and Evil will continue forever in human society, a fact impels us to think more deeply, as we perceive that the essence and goal of our lives is to do our best to push down that which is evil, so that good can rise to the top.

But on reflection we observe an odd thing, that the spiritual hierarchy according to which Good and Evil are distinguished was determined long, long ago, and perhaps arose directly as an instinct inherent in living things: life is good, murder and destruction are evil; love is good, hatred is evil; freedom and ease are good, imprisonment and limitation are evil; invention and development are good, backwardness and lack of progress are bad; being well-fed and warmly clothed is good, hunger and nakedness are bad. One could go on endlessly listing these pairs of good and evil opposites—a sign that the destiny of human beings is unstable, but the experience of living and the spiritual development that goes along with becoming a mature person both affirm the direction that we need to follow and, and show us what things we need to eliminate. This consciousness has created a kind of TRUE DOCTRINE of life, common to all people east and west, ancient and modern.

That people should live in kindness with others and with nature is merely a principle that already lies within the True Doctrine of life, but the reason a person like Trần Văn Thủy had to make a film so as to set this forth as a grave problem of conscience is because life under the system governing the Vietnamese appeared to be lacking in Goodness, and in fact seemed to be inclining toward evil. This was not a question of Good and Evil within an ordinary society, but was the result of the policies of an unusual regime. Due to this, the crisis resulting from the tendency of Evil to suppress Goodness became daily more evident: it became a crisis for the country as a whole.

The film On Being Kind first appeared in 1985—counting back from the present year, 2016, that was thirty-one years ago. So where has the journey of this film and the man who made it brought us by now? The tale of the secret smuggling of this film across Vietnam's border so that it could be shown at the Leipzig film festival at the end of 1988 could be the subject of a breathlessly suspenseful detective film. And when the film's maker slipped across the border to France on the same evening when the film was shown and enthusiastically received at the Leipzig film festival, this was in itself every bit as suspenseful. Only after arriving in France did the film's maker learn that On Being Kindhad won the Silver Dove award at the Leipzig festival. Then it was shown in theaters and on television in France. And after that, many other countries purchased rights to the film and showed it.

When participating in the festival where On Being Kind was shown, Director Trần Văn Thủy stood on a terribly thin, fragile line; either the film would win a prize and he would become a man of achievement who could safely return to Vietnam, or, if the film gained no award at all, he would have no choice but to become an exile in Western Europe.

But "Kindness" smiled on him, and today, at the age of seventy-six, Trần Văn Thủy has consolidated his career with the book Thủy's Craft (Chuyện Nghề Của Thủy), and the book Amid the Heap of Dusty Ashes that you, reader, are now holding in your hands. What Thủy's "heap of dusty ashes" refers to depends on how the reader sees it, but as for the author, I would guess that the name is in some sense a summing up of his personal journey throughout the last fifty years (1966 -– 2016). It doesn't necessarily carry a negative meaning, as when we stand before the remains of a house consumed by fire with nothing remaining but ashes—it is rather the summation of a period encompassing nearly the whole of his life filled with unending vicissitudes on a theme nearly unique: kindness. This "heap of dusty ashes" is merely a manner of speaking, and perhaps includes a suggestion that somewhere in this disorderly heap there may remain a few embers from which Goodness may burst into flame again.

But one thing is for sure; in this heap that the author refers to as "ashes" there lies a heart stirred into a blazing passion by all the events of his life. Many of these events are recounted in this book, and the reader, going through them, will encounter tales of joy and sorrow, memories of past events, nearly all of which have one theme; the elevation of the moral nature of man, a theme that all the great religions have recognized and used to lead humanity. This is perhaps the author's final literary production, for it even contains a "last will and testament" in the chapter "Some Words Left to Others," in which the author gives directions for everything that is to be done after his passing. These words seem very much like the author's Last Wishes, including as they do many concrete instructions for the conduct of his funeral, as well as family and clan matters. At the end of this chapter he writes:

It seems that in this life, there are few if any people who, when they close their eyes and unclench their hands for the last time, do not feel regret for one thing or another. As for me, I regard myself as an ordinary person who has done his best in every situation to do his duty. But my powers are limited; I just feel sorry for the young ones, for our grandchildren. They will come into a meager and scattered inheritance only. It won't be easy for them to enjoy happy lives in the full sense of the expression, such as we of our generation have wished for them.

But in any case, I wish to express the sincere wish that every one of them will be able to live lives full of happiness, and live in the peace and purity of a society that is more honest, more tolerant, than in the past.

What he regrets is that his grandchildren's generation will not be able to enjoy happiness in a complete sense, such as his own generation had wished for them—in other words to live in a society more honest and kind. The word "more" here is full of significance and reflects the sad facts of modern Vietnamese society.

Chapter 2, "My Father," is the essay that I feel is the most important in the book. In recounting the story of his father's life, he clearly states that he is "fondly remembering his teacher"—the man who was his biological and spiritual father—which shows the depth of love and respect with which he regards this figure, who, it seems to me, served as a model, a mirror, for his entire life.

There was one thing his father said that the author, throughout his life, was unable to forget, a sentence calmly uttered after he had witnessed the execution by shooting of a close friend, uncle Phó Mâu, during a "struggle" session.

After the day when he returned to Cồn Market to bury uncle Phó Mâu my father went upstairs to lie down. A moment later, he called me and Lại, my next younger brother, upstairs. The two of us sat and waited for his instructions. He continued lying there, his arm across his forehead, without saying a word. I don't know why, but whenever my father was silent like that, I was very fearful. I spoke to him very quietly:

"What do you have to say to us, father?"

Shortly afterward he uttered one short sentence:

"All — is — ruined, my sons"

I didn't understand. At that time I understood nothing. Again I asked, "What is it you wish to tell us?"

"Uncle Phó Mâu and I helped the Việt Minh in all sorts of ways—and now he has suffered an unjust death! There is nothing left for me to believe in anymore!"

Throughout my life, I have been contually aware of all that my father said to me. This is not the place tell about all of these things, but that sentence, so full of pain and reluctance, "All — is — ruined, my sons" I will surely be unable to forget even as I descend to the grave.

Surely, when a youth hears his father utter such a sentence amid a set of special circumstances in his country, it will become something impossible for him to forget. "All — is — ruined, my sons," a blanket, sweeping expression of a total collapse within the spirit of the father, who conveyed to his sons a consciousness of the future of the society in which they lived, with who nows how much hope that this regime would open up a splendid new period for the country. "All is ruined" was the crucial mark or scar laid down in the soul of the author when he came into adulthood, so that throughout his life he would strive to perceive in what ways society was ruined; and the impression made by this utterance served as a guide to his behavior, so that he could raise a voice of warning to everyone concerning an endlessly tragic crisis threatening an entire people.

In this book, which the author evidently considers his last effort, we feel that the chapter "My Father" is the place where Trần Văn Thủy states what he most fiercely believes in this life, which is the True Doctrine transmitted to him by his father. His father had received this True Doctrine from the age-old traditions of the people of Vietnam, and it was in no way different from the True Doctrine held in common by humanity for thousands of years.

Trần Văn Thủy ponders this basic question in the various other chapters of this book. He is in essence a documentary filmmaker, a man who throughout his career always noted and reduced to writing the various topics that should be made into films—but alas, not many of these intentions of his have turned into realities. In the chapter "Scripts That Didn't Turn Into Films," he records the content of those of his cinematic children who never saw the light of day, mentioning many details, and sometimes expressing rage.

For example, as early as 1980, he had a filmscript about Trịnh Công Sơn:

Another filmscript that pleased me no end was when I wrote about Trịnh Công Sơn in 1980. Perhaps because I had just returned from Russia and had just finished making the well-known film "Betrayal" (1979 – 1980) and was eager for more notariety, I wrote about Trịnh Công Sơn. I wrote about the months and days in which, as I lay in the mouldy tunnels of the southern warfront (1966 – 1969), I would stealthily listen to the Saigon broadcasting station and get gooseflesh as I listened to the songs of Trịnh Công Sơn,hearing such lines as, "The cannons echoing night after night in the city, The streetsweepers suddenly stop their sweeping to stand still and listen; the Vietnamese girl with golden skin… I was obsessed by the people of the South, and the music of Trịnh Công Sơn. How could I have loved it to that extent? Why was I so deeply stirred by it? The problems I laid out in the script didn't have to do only with the mesmerizing melodies and lyrics of Trịnh's music, but centered on a question I asked myself: What was the region, what was the culture, what was the character, that had created this pure and good soul, that had created a person of such sincerity? If, in the words of Karl Marx, "A human individual is a product of the fusion of many social relationships, then why did the society of the South, permeated by the crimes and refuse of the American puppet government—produce a Trịnh Công Sơn?

Thirty years after making On Being Kind to awaken feelings of compassion in the society in which he lived, Director Trần Văn Thủy acknowledges with bitterness that he still lives in the kind of society that provoked him to make the film, but:

Nowadays, under a regime that does everything in the name of excellence, people see no end of regrettable things in the relations of people with each other—greed, factionalism, and dishonest political deals. Virtue has declined to a fearful extent…

Everybody knows that courts and laws serve only to resolve situations that arise as the result of people's actions; if you want to go further and stop the buds of evil from maturing, to eliminate it when it is still in embryo, that is, when it exists only in people's thoughts, then nothing is as good as religion. (…) Religion in the general sense, anything that teaches truth and rectitude, urges people to think of Goodness, to perform acts of Goodness, to avoid evil, to distance themselves from evil. In this way, such teachings make a positive contribution to the enterprise of preserving virtue, order, and stability in society, and makes for a stronger, healthier nation…

Every chapter in this book concerns a matter of interest and, one can say, has an attractive character, but all are suffused with strong feelings that sweep the reader into he discourse. The writer observes the people he knows, together with the joyous and sad things that have happened to him, with great acumen, and when he relates them, all these things turn into lessons for the reader, lessons concerning character, concerning an attitude of living in the world with an unchanging concern: to focus vigorously On Being Kind and compassion.

The author has a very broad range of relations; the topics he writes about range from the filmmaking world of Japan to Americans active in cultural or charitable activities, from making a film about the cathedral complex in Phát Diệm with its unique architecture, to a doctor of rare character who cared for lepers, Dr. Trần Hữu Ngoạn. On finishing the chapter devoted to this last figure, the reader feels constrained to cry out, "There was a saint or a bodhisattva! And he has a chapter on the musician Phạm Duy, whom he revered from the time he was little.

With the sensitive, discerning eye of a documentary film director, along with a spirit that elevates Goodness and opposes Evil, and in addition to this the sharp shrewdness of a person who has lived his life within restrictions, and has always thirsted to tear down the walls surrounding him to promote principles that did not at all accord with the paths taken by the society he lived in, Trần Văn Thủy is entirely worthy of an observation made by the American Larry Berman:

"… it was a war that ravaged so many, yet left us with survivors like Tran Van Thuy, war photographer, filmmaker and ultimately philosopher."

[excerpted from an introduction to the English translation of his autobiography entitled "In Whose Eyes."]

In view of the role Trần Văn Thủy has played, and looking at the society in which he had to live, and at the way in which he drew observations, jidgements, and analyses, so as to tear down the fiendish ideological barbed wire fence in the era in which we live—we can see that, quite apart from his professional role as a filmmaker, he is truly a philosopher, a philosopher who charges into the fray of existence with deep and courageous books and films.

For example, when we watch the film On Being Kind, or at least look at the filmscript, which the director himself wrote, we will see how crucial the ideas in this script are. With no script, the film would be a silent movie; that much is obvious; but what is important are the words that Trần Văn Thủy put into the script. Those words are the soul of the film. They are succinct and easy to understand, but they have a wide application—whatever one sees or hears goes to the heart of the matter, and the film has a special ability to cause the viewer to understand things beyond what he actually sees. Thus, inherent in the script is a philosophy of events and things that raises them to a higher level of generality.

With great rapidity the world caught the significance of the humane signals that Trần Văn Thủy had implanted in the film On Being Kind. In the late 1980s more than ten large television stations throughout the world purchased the rights to the film, and the American John Gianvito named the film as one of the ten best documentary films ever made. Such a thing had never previously happened in the history of Vietnamese cinema.

More than ten years ago Trần Văn Thủy published a book entitled If You Go to the End of All te Seas in which he posed a question both concrete and metaphysical: if you cross all the seas, where will you arrive? Starting at the outset with the concept of a round world, the author expressed the view that, "If you cross all the seas, all the oceans, and cross all the continents, traveling ever onward, ever onward, you will in the end come back to your homeland, to your own village. But many years later, when he went to the United States, only then did he see that the Vietnamese in distant lands had crossed all the oceans, all the continents, going ever onward, but were in the end unable to return to their homelands, their villages.

The newest book, Within the Heap of Dusty Ashes, gives us the impression that the author does not pose that question to hiimself any longer. The geographical road, whether on the face of the earth or the sea, is clear—if you keep going further, you can return to the place you started from. But for the road that passes through people's hearts and all its entanglements with life, one cannot lay down any simple route. The feelings and objectives of the Vietnamese when they thrust their boats into the open sea so as to cross oceans were not such as to make them ask themselves the romantic question about where they could arrive if they went to the end of all the seas. They instead aimed to arrive at some harbor where they could live a free life worthy of a human being. But their lives grew settled in their new surroundings; then, for sure, the road turning back to their homelands still existed in their hearts in many different forms, political, economic, sentimental… and oftentimes only as a dream of returning to a land finer than before, more worthy to be lived in.

But it is surely not the case that the only such road is a concrete one with two directions, going out and coming back, circumscribing our lives. Anyone at all can open numberless roads in his or her heart leading to numberless places that the work Within the Heap of Dusty Ashes itself refers to repeatedly: the road of a kind heart, the road of benevolence. The road of human feeling is wide and vast…

When the musician Phạm Duy wrote the concluding words to his song cycle The Mandarin Road, he depicted the mental state of a Vietnamese who, arriving at the southern peninsula of Cà Mâu, has completed a southward journey through the land's entire length:

My journey has reached its end! The hearts of people are joined!

May you halt here for a moment in joy!

What you have dreamed of now is here!

The road dissolves the borders,

That people may forever

Travel in a realm of feeling everlasting.

The roads of the world lead far

In the hearts of people of all lands.

Could it be that when he wrote these words in the year 1960 Phạm Duy had a presentiment of the roads of the world "leading far" that the Vietnamese people would travel, and that later raised a perplexity with regard to the journey's end in the mind of Trần Văn Thủy? But Phạm Duy also saw the joy to be found in "a realm of feeling everlasting"—could it be that this is the feeling of humanity, of kindness, of love, that Trần Văn Thủy strove to awaken and promote throughout his life, so that it would win out over crudity and evil?

South California, Nov. 1, 2016

Phạm Phú Minh

2- Opening Words

Lời Mở

Dear reader:

When I first had the idea of making this little book I never had the intention of publishing it in the United States. One thing was uppermost in my mind: to try to have it printed in Vietnam; let it be aimed at the people within the country.

On the evening of June 15, 2016 just past I stayed up into the night to finish the draft, because early the next morning I had to go with my children to take my wife to the hospital for an operation on her spinal chord. Spinal chord operations are often attended by misfortune and peril. Furthermore, I knew I would have to lose a long stretch of time staying close to the hospital because of my wife's illness, and my mental state would not permit me to write anything further.

Late that night, according to prior agreement, I was able to send the manuscript to a young friend of mine who worked as an editor in a large publishing house.

It goes without saying that while I was at my wife's bedside, I was also waiting impatiently for a reply from the publishing house with their decision. A week, two weeks, five weeks, eight weeks. And then the awaited event arrived. On August 23, 2016, that is, after a full seventy days, I receved an email message from an editor in the publishing house, conveyed to me by my friend.

Allow me to excerpt the main paragraph below:

…and due to this, in order to print this book, we will have to [the words "have to" offended me, though they belong merely to a verbal formula often used in situations of asking and giving assent in Vietnam]:

- fix up a few sentences in the chapter about your father—this is a minor matter only.

- eliminate Chapter 11 entirely because the discussion concerns a book that is banned in Vietnam, and it is written in the voices of people who are entirely free (a hard thing, because our country is also free).

- Although TVT wrote an appeal concerning this beforehand, it was only through great effort that we were able to retain the two chapters about Cao Xuân Huy and Mộng Giác. As for the chapter in which Anh Vũ discusses Nếu Đi Hết Biển (Chapter 15), this publishing house is unable to print it. With Chapter 15 eliminated, most of Chaptr 16 has no point, so it too must be eliminated except for the words at the end.

Thus about forty pages of the book's 280 pges must be eliminated. With the best will in the world, I cannot do anything other than this. If you have the time, go ahead and read those chapters; you will understand our situation and agree with me immediately. And if you go on and read everything, you will think perhaps that no other publishing house would dare to issue the portion that remains after the cuts.

And so the thing that worried me became a reality—the possibility of publishing the book in Viertnam was closed. Naturally I was sad, and thought about a number of things:

1) I thought that, seen as a publisher's decision, the words "We HAVE TO" cut three chapters (11, 15, 16) and fix three places in Chapter 2 (on my father) were simply beyond my power to endure. Taking stock of the past, I saw that throughout my professional life, perhaps due to indifference, recklessness, trickiness, or even just plain good luck, my films and books, though they went through many vicissitudes, all went forth to the public in their full form: Betrayal, Hanoi In Whose Eyes, On Being Kind, A Story From the Corner of the Park, The Sound of a Violin at Mỹ Lai, There Was a Village, A Spiritual Realm, A Barbarian of Modern Times, Melodies Resounding Through the Ages, If You Go to the Ends of All the Seas, and Thủy's Craft… not a single person, from the prime minister to the general secretary, cabinet ministers, directors, and all the groups of censors had been able to cut a single scene or eliminate a solitary sentence of mine.

I can say with complete truth that, though these works had to go through narrow straits and undergo fierce opposition, all the work that I produced, whether good or bad, all had to survive and go to viewers and readers in their original form. This was a task that was neither simple nor easy. Because of this people call me "Thủy the demon." And I have never in my life gotten mixed up with the "profession" of praise, worship, and celebration of powerful figures.

Because of this, there is now no reason whatsoever, especially now that I am "close to earth and far from heaven," why I should HAVE TO do things contrary to my conscience and my sacred art by agreeing to the dismemberment of my draft in this fashion.

2) I have often reflected that human beings, from the time they learned how to write, from olden times to the present day, have often used this skill to express thoughts and wishes that were good for life and good for humanity. Writing is the same thing as speaking. The creator and various systems of law grant to people, however ignorant and benighted, the right, at a bare minimum, to say what they think. What sort of society is it that doesn't permit people to say what is on their minds? What name should be applied to such a society? What will be the future of such a society?

3) I must ask myself and ask my circle of friends, both gifted and stupid: "Who will say anything in favor of a group of people who have the privilege of "Giving Permission" or "Withholding Perrmission" to people who write or speak? Who?

I cannot avoid feeling a twinge of pain when I recall my early manhood, a full half century ago when, with camera in hand, I filmed scenes in the midst of a terrible war, coming close to death hundreds of times in Vietnam's southern warfront, with corpses next to me, surrounded by smoke and fire, choking for lack of air in tunnels, and consumed with hunger and thirst. How could I have imagined that little toddlers in pants with exposed bottoms or who perhaps had not been born yet, would now hold powers of life or death over the sad or joyous thoughts of this society and over our entire generation? Who? And yet a more important question is: on whose behalf are they acting?

I beg permission now to be a little longwinded:

Perhaps this is due to the occasion a few months hence, when our new prime minister Nguyễn Xuân Phúc fervantly and sincerely made an appeal to build a government "receptive to opinion," a government of "service as opposed to the goverment of "regulators" that had previously been in place—an appeal that was surely stirring and precious, for it expressed the arddnt hopes of the people and a number of individuals in power who care for the country. Let me now confide a few of my thoughts to the publishing houses within the country, and especially with their editors:

I have had the great good fortune to know and respect many of you gentlemen. It is truly something to be treasured when, out of regard for principle, you venture past numerous restrictions to deliver to the public works that are well done, useful, and have a positive effect on the minds and lives of the people in our society.

I understand and am grateful to you!

On the other hand, there are quite a few editors who are deficient in understanding and ability, and do not work in circumstances that allow them to act thus. Often, when dealing with a manuscript that they have read and "have to censor," the concern foremost in their minds is not necessarily whether the work in question is fine and useful for life, but rather: the higher ups, and those still higher up—will they O.K. this? It is a great pity.

Still, I understand you all quite well. When at the tea or beer table, you think the same things I do, speak more skillfully than I do, make jokes and criticise social conditions more sharply than I do. But when faced with a duty assigned to you by a higher up, or when contemplating a bit of salary, quite a few of you have the habit of executing right away the business of the "Virtuous Magistrate and Teacher"—you do this in a very natural and thorough manner.

Why is this the case?

When looking at a manuscript in a friendly spirit, and with a sense of responsibility toward the work and the readers, you try your best, if possible, to work with the author to correct the pages so they will be of more benefit to the world. But if you feel you must act coldly merely from a fear of violating a taboo, or beause you fear going down the wrong road, or that what you are working on is not to the taste of your superiors, and thus are willing to act in the capacity similar to that of an overseer of a jail for political prisoners—then this is a truly sad situation, and there is nothing more to say.

Unseemliness and evil lie precisely in this lack of feeling, this absence of enlightenment. The goodness or evil in a society or in an administrative system are not totally due to its overarching structures (though, granted, the overarching structures in our land decide everything), but arise also from the "little screws" that eagerly perform their duties in such systems and societies.

If I am not mistaken, no one in this country has so far had the ability or enjoyed the circumstances necessary to compile statistics so as to see how much work full of heart's blood and how many useful projects over the half century and more have been thrown into the waste basket, or how many people have been thrown in jail or have had to become refugees in other lands.

How can we build a country that is "receptve to ideas," "devoted to service," and "honest" in a political system that is totalitarian and ridden with graft? I fear that these efforts will automatically turn into a disappointment for Mr Phúc himself, a person whom I am provisionally willing to believe has correct, enlightened, and sincere policies. Just don't leave an opportunity for people to refer to the words of Nguyễn Văn Thiệu with regard to the "speech and actions" of the communists.

Nevertheless, I am also aware that when Mr Phúc makes announcements about "receptivity to opinion," service, and honesty, he is aiming chiefly at administrative and economic problems, and is not necessarily thinking about dilemmas facing the social sciences, and cultural affairs.

I feel no reluctance in speaking of Mr Phúc, because my first film was made diring the war, in the Quảng Nam — Đà Nẵng area—his homeland. In that film, now more than fifty years old, I speak of the endless endurence, surpassing, in an unimaginable fashion, the limits of circumstance, of the people of that region—a monk who lost his pagoda, a little child orphaned, a village girl to whom the unspeakable has happened, an old village teacher and a mother who lost all their children—these were the sorts of things that occurred around Đại Lộc, Hoa Vàng, Duy Xuyên, Điện Bàn, Thăng Bình, and Hội An. That film was entitled The People of My Homeland. Due to this, the brothers, sisters, mothers, and sons of Quảng Nam — Đà Nẵng have long regarded me as one of their own. But whether Mr Phúc regards me as a compatriot or not is anoter matter—back in that time, he was only ten years old.

(I have recorded the war tragedies of that time and place when I was a war journalist in the Quáng region in pages 72 to 127 in the book Thủy's Craft, published by the Writers' Association Press and printed and distributed by Phương Nam Books. That was very possibly the background in which Mr Phúc passed his childhood and early manhood. If you have time, I invite you to read it.)

I sincerely apologize for the length of this digression.

4) I feel that I am old already. I don't have much time left to wait; nor do I have an abundance of strength with which to argue with people, nor am I able to go around making excuses and begging for favors. Due to this, I have had to rely on close friends in the U.S. to help me by allowing me to see this book come into being before it is too late.

So it's all very simple. I'm afraid that if I'm not open and clear about this, who knows, there might be people within the country who will suspect that I am seeking fame and fortune, or who, even more oddly, may accuse me of the crime of "acting in concert with enemy powers abroad." And then there might be some Vietnamese living abroad who might think that this is some kind of propaganda mission for the Vietnamese government (as actually occurred in a "stone throwing" incident that occurred in response to the book If You Go to the ends of All the Seas in California in 2003-2004).

I recall that not long ago Larry Berman, an American historian, came to Hanoi and invited us to participate in a book inauguration event for the Vietnamese translation of his A Perfect Spy that took place in the guest house of the Defense Ministry on Phạm Ngũ Lão Street.

Everyone was radiant, and praised the author, the work, and the personages in the book. I just sat and listened, but then I was the last person asked to make comments. I briefly expressed my feelings with regard to the book and then ventured to express some doubts about the faithfulness of the translation. In front of hundreds of army officers, intelligence men, writers, journalists, a sound recorder, and a movie camera, I gave voice to a number of points that seemed needful to me:

"Larry Berman! Have you looked into the translation of your book The Perfect Spy yet? In your land there is no Ministry of Culture, no Board of Education and Propaganda, and no Central Theoretical Committee, so you can write about whatever is on your mind—while here in Vietnam we have all the bodies that I just referred to, so permit me to say a true word to you, which will also be a word of warning: I do not believe that the Vietnamese translation of the book that you take such pride in has been published in the same form as the original volume. I can guarantee that quite a few places in it have been "castrated," and that it has in general been carefully censored. I looked for evidence of this on the internet before coming to congratulate you." And then, unexpectedly, the room exploded in a round of applause that was longer and louder than any other during the event.

By way of concluding the speech, I added the following:

"Ladies and gentlemen! Please allow me to give vent to a feeling that is often in my thoughts. When God created us, he conferred upon each of us a mouth. That mouth was for the purpose of speaking, of providing us with a means of expressing what we think. There is no reason why the mouth issued to us by God must be used to say things that others wish it to say."

I have repeated this speech "praising God" in many places where I have gone to speak and show films in order to commemorate the thirtieth anniversary of the film On Being Kind. And this speech was especially welcomed when the director of the Catholic Theological Institute in Saigon invited me to speak before six hundred divinity students and various priests and intellectuals. Naturally there is nothing wrong with praising God in a theological school, so I got another great round of applause.

To return to the subject of prohibition and censorship, I beg to state, sincerely and with constructive intent, the following: since the Vietnamese government has itself already promulgated such slogans as "join deeply and widely with the international realm," and "reform the entire system," we should go ahead and do something of great use that is necessary to the advancement of society in Vietnam, a thing that is within our reach and will not cost a thing: and that is to abolish our crude and primitive censorship system, beginning, at the very least, with our current literary and artistic productions. That will be such a constructive step that no words can do justice to it. This step will also serve to remind us that, in an age when information is exploding and globalization is going forward, to continue to apply crude and primitive prohibitions and censorship to artistic works is simply a stupid and ignorant thing, like "carrying a stick to break one's own back."

And then I keep thinking of the cruel colonial government of the French half a century ago when they put into practice a system of censorship only fifty per cent as strict as the present system, a system under which we have no such figures as Nguyễn Công Hoan, Vũ Trọng Phụng, Nam Cao, Ngô Tất Tố, Phạm Quỳnh, Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh… nor do we have such figures as Văn Cao, Phạm Duy, Nguyễn Gia Trí, Trần Văn Cẩn, Tô Ngọc Vân, Bùi Xuân Phải… And after that I am also hard-pressed to come up with a list of illustrious figures like those who appeared in the early 20th century, figures like Phan Chu Trinh, Phan Bội Châu, Nguyễn Thái Học, Hoàng Hoa Thám… and the hundreds and thousands of gentlmen who achieved fame in that era.

Yes indeed! The problem will be very simple if our overriding aim is to act on behalf of humanity, of the people, of the nation, and of the future of this land. And if you need to act on behalf of other things, then please simply say, "Enough! Let's rest easy!" We must fold our arms. Fold our arms and bow, because our generation is old and… cowardly.

Returning now to the circumstances that forced me to publish this "small and insignificant" book, I beg permission to raise my voice in complaint. "Why is the personal status of so many of us Vietnamese so miserable (actually, one must say 'so wretched')? Here I speak only of those who go off to other places: political refugees, economic refugees, reeducation refugees, refugees from political rectitude, prison refugees, refugees from the future, and even cultural refugees, publishing refugees… and the main place of refuge is the United States!

And then I keep on thinking in a romantic manner. It appears that the United States was a "wastebasket" before it became a "heavenly land" to many Vietnamese people. I hope that a few of my books, though they had to go as "refugees" to the United States, will neverthless enjoy equal status with other "refugees"; i.e., that when they return, they will be treated with a little justice, a little kindness.

And so, my dear respected reader! I thank you for holding this book in your hand, and if you feel at all drawn to its content when you read it, then could you be so kind as to help me by bringing the book with you when you go to Vietnam, so you can give it to your reatives and friends—just to read it for fun and get to know it a bit.

There was once a person who wrote the following marvelous observations:

"The soul of a person is a hundred times heavier than his body. It is so heavy that one person cannot carry it. Because of this, when people in this life are still alive, they must try to help each other, so that their souls become everlasting. You help me, I help another. And the other person helps still another person, and so on without end…

I used this passage in the film On Being Kind.

And therefore I feel pain! Pain arising from the fact that this book in your hand contains nothing of great moment, nothing in the way of thunder or lightning. It concerns various matters that actually occurred, small, scattered, and personal, that are related to the social destiny of a person inclined toward Goodness.

I sincerely thank you and my friends near and far who, out of sympathy, have helped me by bringing this book to the hands of readers.

And lastly I ask the reader to forgve me if I have talked about many matters at random, and simply because I have published a very ordinary book.

And I ask to pray for our well-being, for both of us, in fact.

Hanoi; Autumn, 2016

Trần Văn Thủy

PS: When I read these words for my wife to hear, so she could offer suggestions, she was afraid that it might bring troubles—political complications—and tried to dissuade me: "You're old already. Put this matter aside—put the book aside—so you can enjoy some peace." And I felt sadder than ever—discouraged—and didn't know who to complain to. Am I sometimes a timid person? Why must a person feel afraid simply because he has written a few sincere words?

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét